The archetypal division between bites and the whole story played out in the garden of Eden long before Moses returned from the mount with some tablets and a ten chapter yarn, we often thought was missing a few pars.

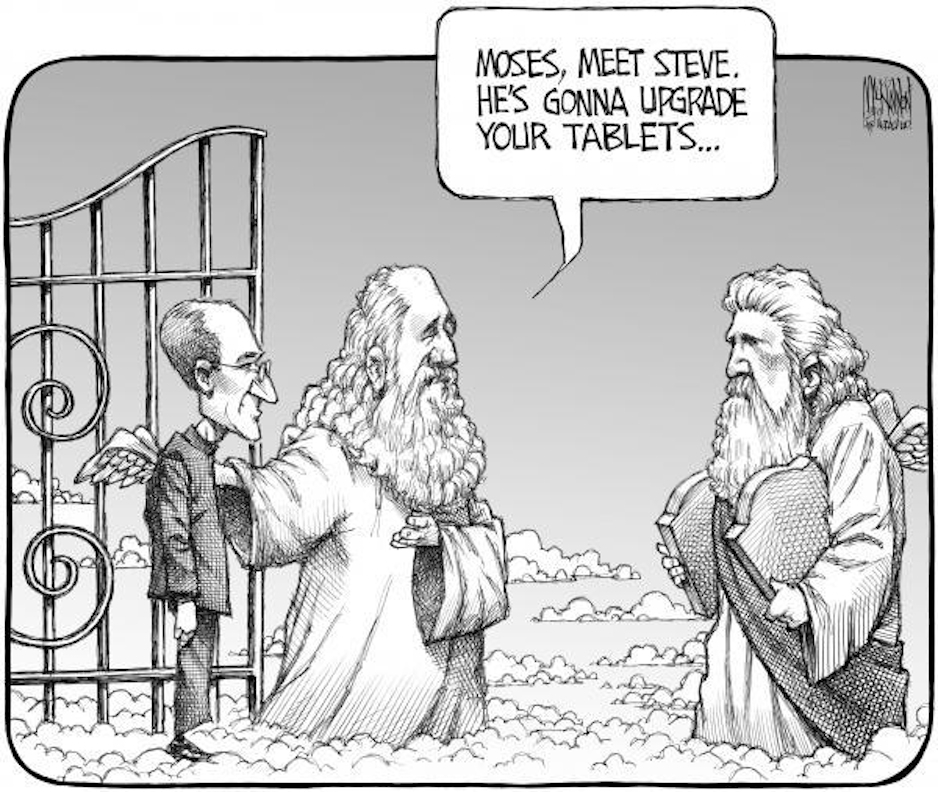

When life gets a bit tough we joke that Moses might have broken a tablet, or two, on the way down the mountain. With only a hammer and chisel and his failing memory he did the best he could to remember the lord’s dictation. Moses recounted the story as best he could. But, if he’d been using one of Steve’s tablets, we may have had a less fragmented story.

The missing commandment dilemma plays out daily and impacts every facet of our life. It played out for me when I arrived at the ABC more than 20 years ago and realized that their charter – their tablets – recommended a more inclusive, less marginalized, more diverse multicultural approach to broadcast than was occurring.

In 1993, I chose to run an experiment at the ABC. I took the watching paint dry obs doc format the poms were producing so well, and re-formatted the style for prime time half hour TV (see Home Truths, Nurses). The aim was to train ordinary citizens to create user-generated content (UGC) that we edited into a series (22 years ago we called this self-shot TV). In essence, we were trying to get a more diverse Australian story, on the ABC.

The first thing that happened, even before we began searching for citizen participants, was the camera department in the Sydney office went on strike. ‘How can we be showing amateur digital DV quality footage on prime time TV (we were on at 8pm:)? It will be our ruin,’ they screamed. On air there was no mention of quality, the viewers were more interested in story.

The point I’m making, slowly, is one that Dino De Laurentis put so eloquently in 1984, “even Dino couldn’t f@#$ a good story”. Story rules, is what el Supremo was saying. In the case of the ABC experiment, the viewers put up with DV quality because the self-shot nature of the story was unique. Dino went on to tell us that people will always watch a great story, and he was right.

How does all this play out with mojo?

Firstly, there are many great mojo trainers chatting online. Some focus heavily on tech, others lean on story. A predisposition, either way, appears to depend on the trainers background. The trainer with a tech, radio or print background, will generally be more rigid and advocate a techno-deterministic view of mojo. In essence, this view strives for a technical look that would put mojo in competition with content delivered by mainstream crews.

My background as a journalist, a cameraman and as an executive producer, on countless TV series, informs my view about mojo. So does my story telling and location based experience as a producer and occasional camera person on international current affairs series like Foreign Correspondent. It’s only natural that we are all the product of our experience. But if that’s true then we all bring to the table a particular way of seeing and doing – a varied appreciation of what’s possible.

I have always been quite tech-savy, but my focus is story, or more correctly finding a balance between story and tech. It’s not a techno-deterministic digital sublime way of thinking, which posits that tech is the complete answer, but a neo-journalistic approach that informs a holistic mojo philosophy.

What I look for when I begin my training programs is a link between what journalists know and what I’m teaching, and invariably, that’s story. I look for the same connection when I work with citizens and students. This link forms the basis of our conversation. Without story there is no mojo.

When I’m training journalists in a print, shifting to digital, broadcast environment, I find there are a number of factors that impact traction (a) digital skill lag, (b) a techno determinist approach, and (c) time credits. Story is a journalists stock in trade. When I wrote in this article about Ekstra Bladet’s conversion to digital and web TV, journalists were most concerned about digital storytelling impacting adversely on the time they have to do their job properly. In the main that’s telling stories, not pressing buttons, even though today the two are becoming more linked.

This focus on story has worked for me. Print houses loving that their journalists are seeing their mojo video training as fun and producing it voluntarily. News bosses are seeing a growth in self-esteem and confidence, to a point where one major news room informs me that their newly trained mobile journalists are checking their own online statistics. At another media house 25-30% of journalists who did the mojo training program are producing 1 to 2 complete edited mobile videos each week. Another 50% of those journalists produce 1-2 videos each month. Those of us involved in mobile conversion know how difficult it is to get traction – so these results are encouraging. At Shibsted media, one group of journalists, who did the Smartmojo course, impressed their bosses so much with their new video skills, that management offered to buy them all new mojo gear.

Mobile technology is a conduit between story and a global conversation. There’s no denying the impact of technology on communications and no denying that the new news room is a mobile active space. Being a professional journalist means being able to use mobile. If this is true then what do we call a citizen journalist who uses a mobile to tell complete UGS? If there is a difference, then what is it?

Citizen journalist or citizen witness?

The notion that citizen journalism can immediately result from someone having a picnic on the banks of the Hudson river, who snaps a plane crashing into its icy waters, is underwhelming and undervaluing citizen journalism, and the citizen’s role as participants in the journalistic conversation. That citizen witness, is citizen journalism, is a commonly held view that can be true, depending on the nature and the augmentation of the citizen witness UGC. It is also a view that organisations like CNN espouse. One reason is that formats like iReport provide CNN with free content, which they call citizen journalism. This promote this view partly to justify their free use of iReport footage across programs. Citizens submitting content to iReport need to sign an complex contract that enables CNN to use their footage in any CNN program. The CNN iReport TOU states:

“By submitting your material, for good and valuable consideration, the sufficiency and receipt of which you hereby acknowledge, you hereby grant to CNN and its affiliates a non-exclusive, perpetual, worldwide license to edit, telecast, rerun, reproduce, use, create derivative works from, syndicate, license, print, sublicense, distribute and otherwise exhibit the materials you submit, or any portion thereof in any manner and in any medium or forum, whether now known or hereafter devised, without payment to you or any third party.”

Not withstanding the service that iReport might perform, can it be true that iReporters give those rights away just by submitting material for consideration, and even if it is not broadcast? Of course if CNN sell iReport material to a third party they’ll pay something after costs but people who submitted material to iReport don’t get any compensation for the use and re-use of their content unless CNN make some profit on the sale of that material. The irony is that if you are a community who sees something interesting on CNNs iReport and wishe to use it for your ow community initiative, you will first need to get permission from CNN, who now expressly state that they own a copyright in the selection, coordination, arrangement and enhancement of such content, as well as in the content original to it’.

Now, if you use your smartphone to edit your UGC into UGS, it may not get a run on CNNs iReport, becasue it’s not raw footage which is easier to augment, badge or voice and which works best for lacing into CNN stories and programs. By creating UGS and not just UGC citizens maintain diversity at source and more control over their message and their content, which by the way, can be sold, possibly even to CNN for use on World Report – but that’s another story.

Hence, technology will help capture, edit and disseminate content, but your ability to create story – to transform UGC into UGS – will maximise your potential to create a less marginalised and more democratic public sphere – for your voice to be heard.

No comments yet.